Who this is for: Security engineers, penetration testers, and software architects who want to understand why certain vulnerability classes exist rather than just memorizing exploitation techniques. Familiarity with basic programming concepts is assumed.

TL;DR: SQL Injection, XSS, and similar vulnerabilities are not random bugs, they are predictable consequences of using the wrong computational model to parse input. Regular expressions cannot recognize nested structures like HTML or SQL. Using regex to filter context-free data is mathematically impossible. This post explains the theory behind this limit and shows how to apply it to real security problems.

Introduction

Security practitioners categorize vulnerabilities by their effects: Cross-Site Scripting, SQL Injection, Command Injection, HTTP Request Smuggling. These categories describe symptoms, but they share a common underlying cause rooted in computation theory. At their core, these vulnerabilities represent failures in how systems parse and interpret input data.

When we build software, we implicitly define a language that the software accepts. An SQL query follows a grammar. An HTTP request adheres to a specification. A JSON document has rules about structure and nesting. Problems arise when the language that developers think their software accepts differs from the language their software actually accepts.

This gap between intended and actual behavior is the domain of Language Theoretic Security (LangSec), a discipline that applies formal language theory to security. LangSec's central insight is captured in a single phrase:

"The road to hell is paved with ad-hoc parsers."

When developers treat complex structured data as simple strings and attempt to sanitize it with pattern matching, they are attempting the mathematically impossible. To understand why, we need to examine the foundations of computational theory.

Background: Formal Language Theory

Formal language theory provides the mathematical foundation for understanding what computers can and cannot process. Developed primarily by Noam Chomsky in the 1950s, this framework classifies languages into a hierarchy based on their computational complexity.

What is a Formal Language?

A formal language is simply a set of strings over some alphabet. The alphabet might be ASCII characters, binary digits, or any other finite set of symbols. The language defines which combinations of those symbols are "valid" according to some rules.

For example, the language of valid email addresses includes strings like user@example.com but excludes @@invalid. The language of valid JSON documents includes {"key": "value"} but excludes {key: value} (missing quotes). Every protocol, data format, and programming language implicitly defines a formal language.

Formal Grammars: Production Rules

Languages are specified using grammars; sets of rules that generate all valid strings. A grammar consists of:

- Terminal symbols: The actual characters that appear in strings (like

a,b,0,1) - Non-terminal symbols: Placeholders used during derivation (like

S,A,B) - Production rules: Rules that replace non-terminals with other symbols

- Start symbol: The initial non-terminal from which derivation begins

Consider a simple grammar for generating balanced parentheses:

S → (S)

S → SS

S → ε

Here, S is the start symbol, ( and ) are terminals, and ε represents the empty string. This grammar generates strings like (), (()), ()(), and ((())).

To derive (()):

S → (S) → ((S)) → (())

The Chomsky Hierarchy

The Chomsky Hierarchy classifies grammars into four levels based on the restrictions placed on production rules. Each level corresponds to a specific type of computational machine required for recognition.

The diagram above shows the key property of the hierarchy: proper containment. Every regular language is context-free. Every context-free language is context-sensitive. But the reverse is not true as there are context-free languages that are not regular, and context-sensitive languages that are not context-free.

Type 3: Regular Languages

Regular languages are the simplest class, recognized by Finite Automata (FA). Production rules in a regular grammar must have the form:

A → aB (non-terminal produces terminal followed by non-terminal)

A → a (non-terminal produces terminal)

A → ε (non-terminal produces empty string)

A grammar for strings ending in "ab":

S → aS | bS | aA

A → b

This generates: ab, aab, bab, aaab, abab, etc.

Constructing the Automaton from the Grammar:

Converting a regular grammar to a finite automaton follows a systematic procedure taught in compilation courses. The grammar maps directly to a non-deterministic finite automaton (NFA), which we then convert to a DFA using subset construction.

Step 1: Grammar to NFA

Each non-terminal becomes a state. The start symbol becomes the start state. Productions of the form A → a (terminal only) lead to a new accept state.

Recall the grammar from above:

Sis the start symbolAis an intermediate non-terminal- The productions are:

S → aS | bS | aAandA → b

From these productions, we create NFA transitions:

S → aScreates transition:S --a--> SS → bScreates transition:S --b--> SS → aAcreates transition:S --a--> AA → bcreates transition:A --b--> (accept)

This NFA is non-deterministic because from state S, reading 'a' can lead to either S or A.

Step 2: Subset Construction (NFA to DFA)

To convert the NFA to a DFA, we compute the set of NFA states reachable for each input. Each set of NFA states becomes a single DFA state.

Starting from {S}, we compute:

| DFA State | On 'a' | On 'b' |

|---|---|---|

{S} | {S, A} | {S} |

{S, A} | {S, A} | {S, accept} |

{S, accept} | {S, A} | {S} |

Step 3: Draw the DFA from the Table

Renaming the states for clarity:

- q₀ =

{S}(start state) - q₁ =

{S, A}(saw 'a', might be ending) - q₂ =

{S, accept}(accept state, just saw "ab")

The transition table becomes:

| State | 'a' | 'b' |

|---|---|---|

| q₀ | q₁ | q₀ |

| q₁ | q₁ | q₂ |

| q₂ (accept) | q₁ | q₀ |

This table directly maps to the state diagram below. Each row is a state, each cell is a transition arrow labeled with the input symbol.

The key property of regular languages is that they require no memory to recognize. A finite automaton reads input one symbol at a time, transitions between a finite number of states, and accepts or rejects based solely on the final state reached.

The automaton above accepts strings ending in "ab". Try inputs like ab, bab, aab, or ba to see how the machine transitions. Notice that it has no way to "remember" what it saw earlier, so only the current state matters.

Security Implication: Regular languages are tractable to process safely, provided deterministic or linear-time automata are used. Recognition takes O(n) time with no recursion or stack exhaustion. However, note that many "regex" engines (PCRE, Python's re) include backtracking features that can cause catastrophic performance (ReDoS) on pathological inputs. True safety requires DFA-based matching or careful pattern design.

Practical Uses: Validating simple tokens; IP addresses, UUIDs, basic email patterns, date formats.

A note on "regex" vs. regular languages: Modern regex engines often include backtracking, recursion, lookahead, and backreferences that go beyond regular languages. These features effectively embed a parser and reintroduce complexity, performance risks, and ambiguity. The LangSec argument still holds: if you need these features, you needed a parser, not a filter.

Type 2: Context-Free Languages

Context-free languages require a more powerful machine: the Pushdown Automaton (PDA), which adds a stack memory to the finite automaton. Production rules have the form:

A → α (where α is any string of terminals and non-terminals)

A grammar for balanced brackets:

S → [S]

S → SS

S → ε

A grammar for the language aⁿbⁿ (equal a's followed by b's):

S → aSb

S → ε

This generates: ε, ab, aabb, aaabbb, etc. The key property is that this language cannot be recognized by any finite automaton. No matter how many states you add, a finite automaton cannot count arbitrarily large numbers of as to match against bs.

Solving the Balanced String Problem with a Stack

The language L = { aⁿbⁿ | n ≥ 0 } requires memory. Specifically, it requires a stack; a last-in-first-out data structure. Here is how a pushdown automaton solves this problem:

Algorithm:

- Start with an empty stack (containing only the bottom marker

Z) - For each

ain the input:- Push symbol

Aonto the stack

- Push symbol

- When we see the first

b:- Switch to "matching mode"

- For each

bin the input:- Pop one

Afrom the stack - If stack is empty (only

Zremains) and we see anotherb, reject (too many b's)

- Pop one

- At end of input:

- If stack contains only

Z, accept (balanced) - If stack contains unmatched

As, reject (too many a's)

- If stack contains only

The stack serves as a counter. Each a adds to the count; each b decrements it. The string is balanced if and only if the count returns to zero at the end.

The pushdown automaton above implements this algorithm. Try aabb (accepted), aaabbb (accepted), aab (rejected: too many a's), abb (rejected: too many b's). Watch how the stack grows when reading as and shrinks when reading bs.

Security Implication: Most structured data formats; JSON, XML, HTML, SQL, and programming languages are context-free. They require proper parsers with stack-based memory. Regular expressions cannot recognize them correctly.

Common Parsing Conflicts

When building parsers for context-free languages (using tools like Yacc/Bison or PLY), you will encounter two types of conflicts. These signal that your grammar is ambiguous or requires more lookahead than the parser supports.

1. Shift/Reduce Conflicts The parser cannot decide whether to shift the next token onto the stack or reduce the current stack items using a grammar rule.

- Classic Example: The "Dangling Else" problem.

When the parser seesIF expr THEN stmt IF expr THEN stmt ELSE stmtIF a THEN IF b THEN c ELSE d, and is at theELSE, it doesn't know if theELSEbelongs to the innerIF(shift) or if the outerIFis finished (reduce). - Resolution: Most parsers default to "shift" (binding the

ELSEto the nearestIF), which is usually correct.

2. Reduce/Reduce Conflicts The parser has a valid match on the stack for multiple different rules and doesn't know which one to apply.

- Example: A grammar that distinguishes "Usernames" from "Nicknames" purely by context, but defines them identically.

If the parser sees ausername -> WORD nickname -> WORDWORD, it doesn't know whether to reduce it to ausernameor anicknamewithout more context. - Significance: These are almost always serious errors in grammar design. They indicate that your language definition overlaps in a way the parser cannot disambiguate.

When do they appear?

- Ambiguous Syntax: When a string has two valid parse trees (e.g.,

1 + 2 * 3without operator precedence). - Lookahead Limitations: LALR(1) parsers (like PLY) only look one token ahead. If disambiguation requires seeing 2+ tokens, a conflict occurs.

- Solution: Rewrite the grammar to be unambiguous or use precedence rules. Note that Shift/Reduce is often a warning (default behavior works), while Reduce/Reduce is an error.

Type 1: Context-Sensitive Languages

Context-sensitive languages are recognized by Linear Bounded Automata (LBA); Turing machines whose tape length is limited to a linear function of the input length. Production rules have the form:

αAβ → αγβ (A can only be replaced when surrounded by α and β)

The classic example is L = { aⁿbⁿcⁿ | n ≥ 0 }. This language requires matching three groups, which cannot be done with a single stack. You need more sophisticated memory structures.

Real-world examples in security:

- Protocol length fields: HTTP's

Content-Lengthheader must match the actual body size. Verifying this correspondence requires memory proportional to the input. - Cross-field validation: A certificate's

issuerfield in one structure must equal thesubjectfield of another. These cross-references create context-sensitive constraints. - Type systems: Many programming languages have type systems that enforce context-sensitive properties (variable names must be declared before use, types must match across expressions).

Security Implication: Context-sensitive constraints are decidable (unlike Type 0) but computationally expensive, membership is PSPACE-complete in the general case. Attackers can sometimes exploit the gap between what a fast-path validator checks and what the full context-sensitive grammar requires.

Type 0: Recursively Enumerable Languages and Turing Machines

The most powerful computational model is the Turing Machine. Understanding Turing machines is essential for understanding fundamental limits on what any algorithm,including security tools, can accomplish.

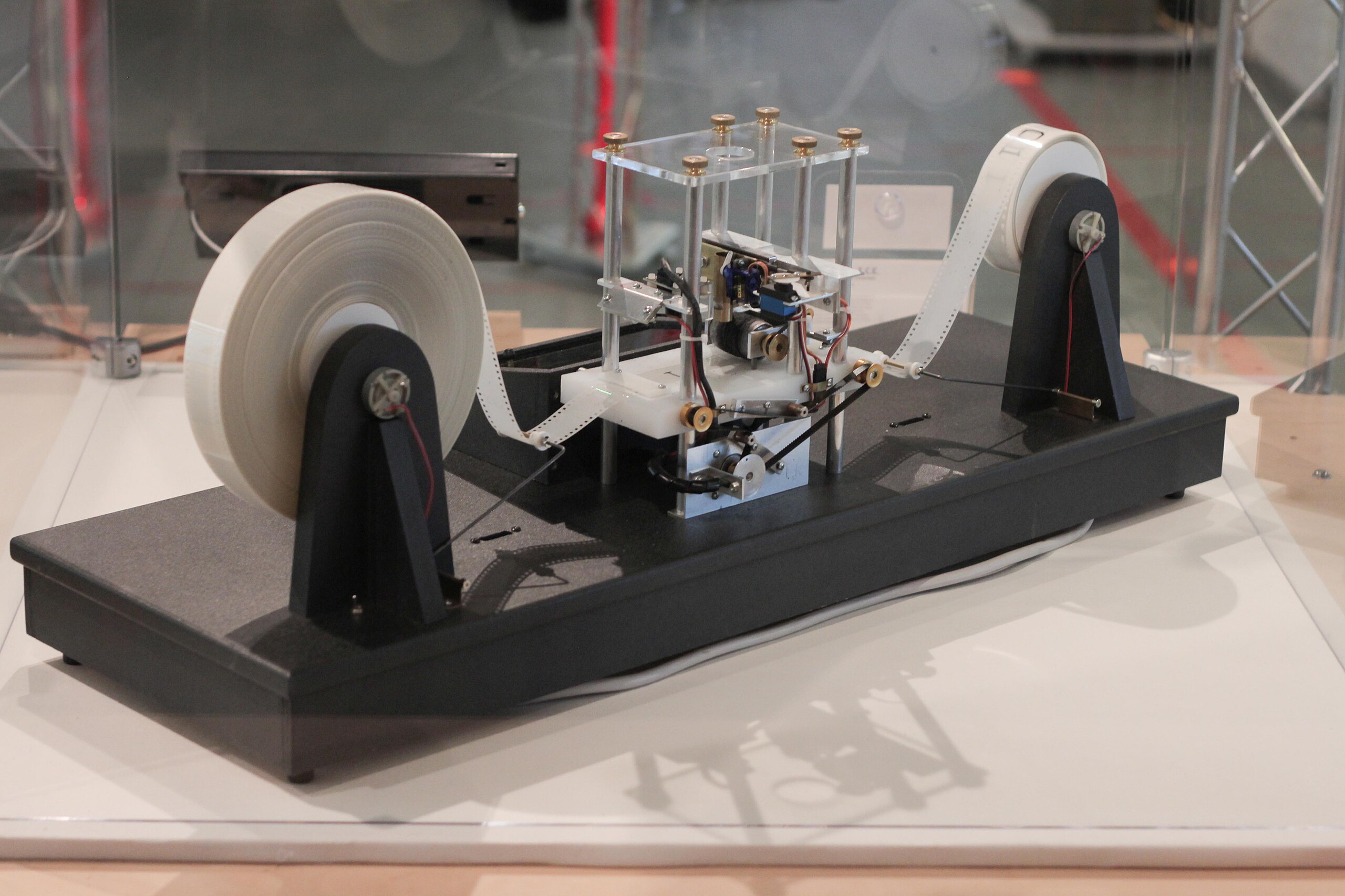

What is a Turing Machine?

A Turing Machine consists of:

- An infinite tape divided into cells, each holding a symbol

- A head that reads and writes symbols, moving left or right

- A finite set of states

- A transition function that determines the next action based on current state and symbol read

Tape: ... □ □ [a] a b b □ □ ...

↑

Head

State: q0

Transition: (q0, a) → (q1, X, R)

"In state q0, reading 'a': write 'X', move Right, go to state q1"

The Turing Machine can simulate any algorithm. If a problem can be solved by any computational process, it can be solved by a Turing Machine. This is the Church-Turing Thesis.

The Halting Problem

Here is the fundamental limit: no algorithm can determine whether an arbitrary Turing Machine will halt on a given input.

This is proven by contradiction. Suppose a "halt detector" H exists:

H(program, input) → "halts" or "loops forever"

Construct a program D that does the opposite of what H predicts:

def D(program):

if H(program, program) == "halts":

loop_forever()

else:

halt()

Now ask: does D(D) halt?

- If H says D(D) halts, then D loops forever (contradiction)

- If H says D(D) loops, then D halts (contradiction)

Therefore, H cannot exist.

Security Implications of Undecidability

The halting problem has profound implications for security:

You cannot build a perfect malware detector. No static analyzer can determine whether an arbitrary program is malicious without running it. Malware authors can always construct code that defeats any detection algorithm.

You cannot validate Turing-complete inputs. If your application accepts input that can express arbitrary computation (Python scripts, serialized objects, macros), no validator can guarantee safety. The only options are:

- Sandbox the execution

- Restrict the input language to a decidable subset

- Accept the risk

Antivirus is fundamentally limited. This is not a failure of implementation, it is a mathematical impossibility. Defenders must rely on heuristics, sandboxing, and behavior monitoring because perfect static detection is provably impossible.

Closure Properties

Formal languages have closure properties that determine how operations affect language class:

| Operation | Regular | Context-Free |

|---|---|---|

| Union | Closed | Closed |

| Concatenation | Closed | Closed |

| Kleene Star | Closed | Closed |

| Intersection | Closed | Not closed |

| Complement | Closed | Not closed |

The non-closure of CFLs under intersection has security implications: even if two filters each accept only "safe" context-free inputs, their combination might not.

Building Programming Languages: The Compiler Pipeline

Understanding language processing requires examining how compilers and interpreters work. The translation from source code to executable form proceeds through distinct phases, each operating on a different representation of the program.

Phase 1: Lexical Analysis (Tokenization)

The lexer (or scanner) reads raw source characters and groups them into tokens; meaningful units like keywords, identifiers, operators, and literals.

Consider this SQL fragment:

SELECT name FROM users WHERE age > 18

The lexer produces a token stream:

KEYWORD:SELECT IDENTIFIER:name KEYWORD:FROM IDENTIFIER:users

KEYWORD:WHERE IDENTIFIER:age OPERATOR:> INTEGER:18

Lexers are typically implemented as finite automata because individual tokens are regular languages. The following pseudocode demonstrates the concept:

class Token:

def __init__(self, type: str, value: str):

self.type = type

self.value = value

The tokenizer scans through the input string character by character:

def tokenize(input_string: str) -> list[Token]:

tokens = []

i = 0

while i < len(input_string):

char = input_string[i]

Whitespace is skipped without producing tokens:

if char.isspace():

i += 1

continue

Alphabetic characters begin either keywords or identifiers. The lexer reads the entire word and then checks against a keyword list:

if char.isalpha():

word = ""

while i < len(input_string) and input_string[i].isalnum():

word += input_string[i]

i += 1

if word.upper() in ("SELECT", "FROM", "WHERE", "AND", "OR"):

tokens.append(Token("KEYWORD", word.upper()))

else:

tokens.append(Token("IDENTIFIER", word))

continue

Digits begin numeric literals:

if char.isdigit():

num = ""

while i < len(input_string) and input_string[i].isdigit():

num += input_string[i]

i += 1

tokens.append(Token("INTEGER", num))

continue

Single-character operators are recognized directly:

if char in "><=!":

tokens.append(Token("OPERATOR", char))

i += 1

continue

i += 1

return tokens

Security Relevance: The boundary between tokens is where injection attacks occur. When user input is concatenated into a query string before tokenization, the attacker can inject characters that the lexer interprets as token boundaries, transforming data into code.

Phase 2: Parsing (Syntactic Analysis)

The parser reads the token stream and builds an Abstract Syntax Tree (AST) representing the program's grammatical structure. Parsers implement context-free grammars.

A simplified SQL grammar:

Query → SELECT Columns FROM Identifier WhereClause?

Columns → Identifier | '*'

WhereClause → WHERE Condition

Condition → Identifier Operator Value

Value → Identifier | Integer | String

The parser verifies that tokens appear in valid sequences according to this grammar. If the input violates the grammar, parsing fails with a syntax error.

Security Relevance: SQL injection succeeds when attacker input changes the shape of the AST. Parameterized queries prevent this by separating the query structure (parsed once) from the data values (substituted later).

Phase 3: Semantic Analysis

Semantic analysis verifies meaning beyond syntax: type checking, scope resolution, and constraint validation. A syntactically valid program might be semantically invalid:

SELECT age FROM users WHERE name > 18

This is syntactically correct but semantically problematic, comparing a string column to an integer.

Security Relevance: Many vulnerabilities arise from semantic gaps. A WAF might parse input syntactically but miss semantic violations that the backend interprets differently.

Phase 4: Code Generation and Execution

Finally, the compiler generates executable code or the interpreter directly executes the AST. At this stage, the abstract representation becomes concrete behavior.

Applications of Parsers in Information Security

The parsing pipeline is not merely academic, it has direct, practical applications in security operations. Teams that understand formal language theory can build more robust tools, detect more sophisticated attacks, and analyze complex malicious artifacts.

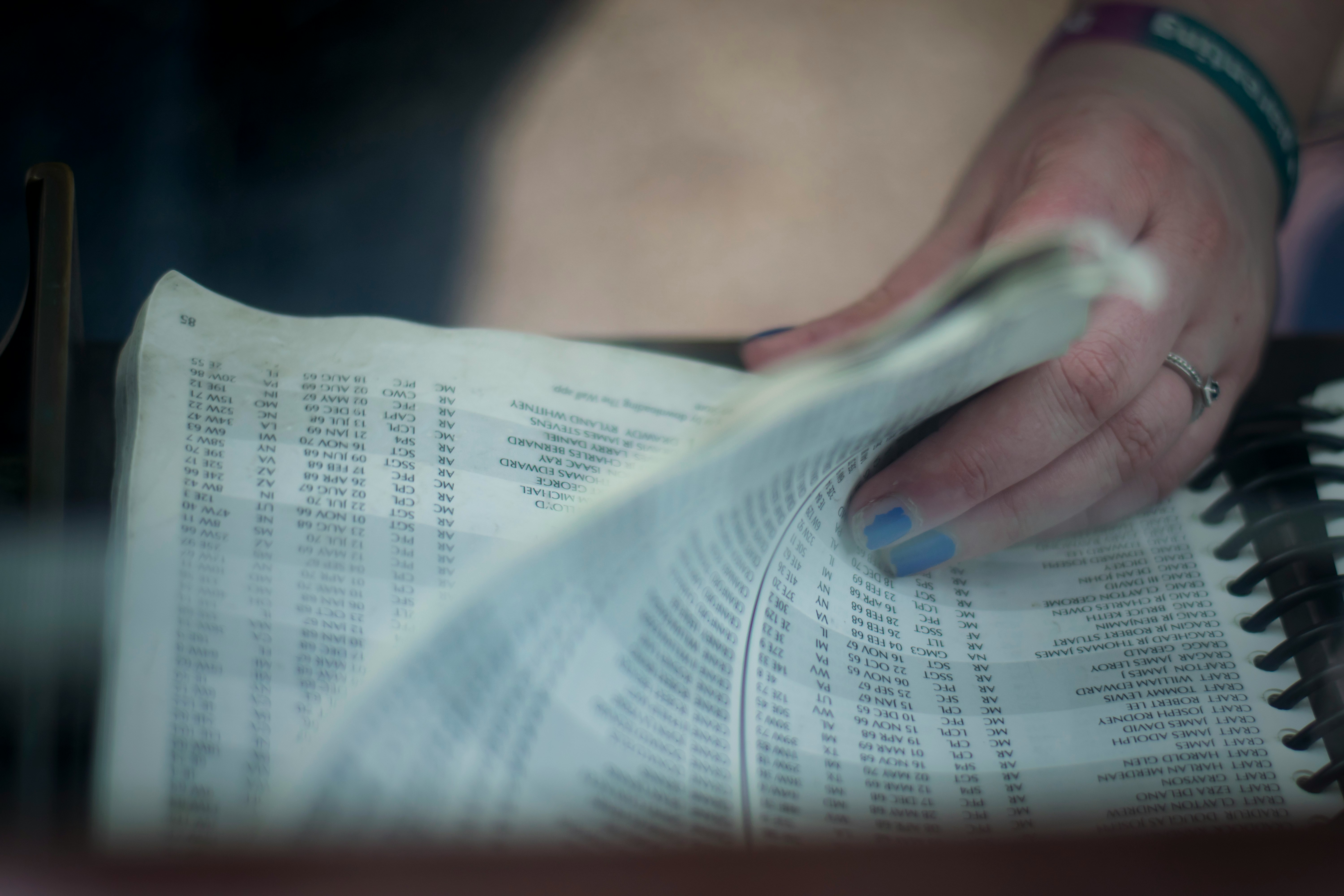

Parsing Stealer Logs

Information stealers (RedLine, Vidar, Raccoon, Lumma) exfiltrate credentials, cookies, and system data from compromised machines. This data follows predictable formats, making it amenable to grammar-based parsing.

A typical stealer log might contain:

=== Chrome Passwords ===

URL: https://bank.example.com/login

Username: victim@email.com

Password: p@ssw0rd123

=== System Info ===

OS: Windows 10 Pro

IP: 192.168.1.100

HWID: ABC123...

Each stealer family has its own format, but they share common structures:

StealerLog → Section*

Section → SectionHeader Entry*

SectionHeader → '===' SectionName '===' NEWLINE

Entry → Key ':' Value NEWLINE

Key → IDENTIFIER

Value → TEXT

A grammar-based parser provides several advantages over ad-hoc regex parsing:

Robustness: The parser handles variations in whitespace, encoding, and formatting that would break fragile regex patterns.

Extensibility: Adding support for a new stealer family requires defining its grammar, not rewriting extraction logic.

Structured output: The parser produces a typed AST that can be directly processed, enriched, and stored.

class StealerLogParser:

"""

CFG-based parser for stealer log formats.

Produces structured output suitable for threat intelligence.

"""

def __init__(self, log_content: str):

self.content = log_content

self.pos = 0

self.sections = []

The parser first tokenizes section headers:

def parse_section_header(self) -> str | None:

"""Match section headers like '=== Chrome Passwords ==='"""

match = re.match(r'===\s*(.+?)\s*===', self.content[self.pos:])

if match:

self.pos += match.end()

self.skip_whitespace()

return match.group(1)

return None

Then extracts key-value entries:

def parse_entry(self) -> tuple[str, str] | None:

"""Match entries like 'URL: https://...'"""

match = re.match(r'(\w+):\s*(.+?)(?=\n|$)', self.content[self.pos:])

if match:

self.pos += match.end()

self.skip_whitespace()

return (match.group(1), match.group(2))

return None

The main parsing loop applies production rules:

def parse(self) -> dict:

"""Parse the entire log into structured sections."""

result = {}

while self.pos < len(self.content):

header = self.parse_section_header()

if header:

entries = {}

while True:

entry = self.parse_entry()

if entry is None:

break

entries[entry[0]] = entry[1]

result[header] = entries

else:

self.pos += 1 # Skip unrecognized content

return result

Note on regex usage: The

re.match()calls above act as token recognizers (lexer-level helpers) within the grammar-driven parsing loop, not as validation logic for the entire format. This is analogous to how compilers use regex/DFA to identify tokens, then use a CFG parser for structure. The key architectural point is that the grammar defines what constitutes a valid log, and the regexes only identify individual terminals.

This approach scales to multiple stealer families by defining family-specific grammars and composing them.

Malware Configuration Extraction

Many malware families embed configuration data in structured formats; encrypted JSON, custom binary formats, or registry-style key-value stores. Grammar-based parsing enables systematic extraction.

Consider a hypothetical C2 beacon configuration:

[config]

server=https://c2.evil.com:443

sleep=60

jitter=0.2

[commands]

whoami=c2_cmd_1

download=c2_cmd_2

The grammar:

Config → Section*

Section → '[' SectionName ']' NEWLINE Setting*

SectionName → IDENTIFIER

Setting → Key '=' Value NEWLINE

A parser built from this grammar extracts configurations reliably, regardless of whitespace variations or ordering.

Protocol Dissection

Network protocols follow grammars. HTTP, DNS, TLS, and custom C2 protocols all have formal or informal specifications that define valid message structures.

When analyzing unknown C2 protocols, security researchers:

- Capture network traffic

- Identify invariant structures (magic bytes, length fields)

- Hypothesize a grammar that generates observed messages

- Test the grammar against additional samples

This is essentially formal language inference applied to malware analysis.

Building Security Tools with Parser Generators

Parser generators like ANTLR, PLY (Python Lex-Yacc), or tree-sitter produce parsers from grammar specifications. Security teams can use these to build:

- Custom log analyzers that handle domain-specific formats

- Configuration validators that enforce schema compliance

- Protocol fuzzers that generate grammar-conforming but adversarial inputs

- Source code analyzers that detect vulnerable patterns

The grammar becomes documentation; the generated parser becomes the enforcement mechanism.

Why Regex Fails: A Formal Proof Sketch

The Pumping Lemma for Regular Languages proves that regular languages cannot express unbounded counting. For any regular language L, there exists a pumping length p such that any string s in L with |s| ≥ p can be split into xyz where:

- |y| > 0

- |xy| ≤ p

- For all n ≥ 0, xy^n z is in L

The language of balanced parentheses { (^n )^n | n ≥ 0 } violates this lemma. Any attempt to pump (repeat) a middle section produces unbalanced strings. Therefore, no regex can recognize balanced parentheses.

Practical consequence: No regex-based WAF can correctly filter HTML, SQL, or any other context-free language. Attackers can always find inputs that the regex accepts but the backend interprets maliciously.

Practical Examples: Theory in Action

SQL Injection: Token-Level Attack

Consider the tokenization of a malicious input:

username = "admin' OR '1'='1"

query = f"SELECT * FROM users WHERE name = '{username}'"

The constructed query string:

SELECT * FROM users WHERE name = 'admin' OR '1'='1'

Token stream produced by the SQL lexer:

KEYWORD:SELECT OPERATOR:* KEYWORD:FROM IDENTIFIER:users

KEYWORD:WHERE IDENTIFIER:name OPERATOR:= STRING:'admin'

KEYWORD:OR STRING:'1' OPERATOR:= STRING:'1'

The attacker's input (admin' OR '1'='1) was intended to be a single STRING token. Instead, the closing quote terminated the string early, and subsequent characters became KEYWORD, STRING, and OPERATOR tokens. The input escaped from the data plane into the control plane.

Parameterized queries solve this at the protocol level:

query = "SELECT * FROM users WHERE name = ?"

cursor.execute(query, [username])

The query structure is parsed once; the parameter is substituted after parsing. The parameter cannot affect token boundaries because the tokenization already happened.

XSS: Context-Switching Attack

HTML parsing is more complex because it involves multiple nested languages (HTML → CSS → JavaScript). An XSS vulnerability exploits transitions between these contexts.

<div class="user-bio">{{user_input}}</div>

If user_input contains </div><script>alert(1)</script><div>, the browser's HTML parser sees:

<div class="user-bio"></div><script>alert(1)</script><div></div>

The </div> closes the bio div, <script> begins a script element, and the JavaScript engine executes alert(1).

A regex filter for <script> fails against:

<scr<script>ipt>alert(1)</script>

The regex removes <script>, leaving:

<script>alert(1)</script>

The HTML parser, being context-free, correctly recognizes the tag. The regex, being regular, cannot.

Defense Strategies Informed by Language Theory

1. Match Parser Power to Input Complexity

| Input Type | Language Class | Appropriate Tool |

|---|---|---|

| UUID | Regular | Regex |

| IP Address | Regular | Regex |

| Email (basic) | Regular | Regex |

| JSON | Context-Free | json.parse() |

| XML/HTML | Context-Free | DOM Parser |

| SQL | Context-Free | Parameterized Queries |

| Python/JS/etc. | Turing-Complete | Sandboxed Execution |

2. Validate Early, Parse Once

Parse input at the system boundary and pass the structured representation (AST, DOM, typed object) internally. Never re-parse string representations downstream.

# Bad: String passed through, re-parsed by each layer

def process_request(json_string: str):

layer1_process(json_string)

layer2_process(json_string)

# Good: Parse once, pass structure

def process_request(json_string: str):

data = json.loads(json_string) # Parse at boundary

layer1_process(data) # Receive typed dict

layer2_process(data) # Same typed dict

3. Minimize Input Language Power

If you're designing a configuration format, choose the simplest language class that meets your needs:

- Need simple key-value pairs? Use a regular language.

- Need nested structures? Use a context-free language (JSON, TOML).

- Need computation? Reconsider your requirements.

Avoid formats that are accidentally Turing-complete (YAML with arbitrary object construction, XML with external entities).

4. Test Parser Boundary Cases

Systematic testing should include:

- Inputs at the boundary between valid and invalid

- Deeply nested structures (stack exhaustion)

- Unusual but technically valid encodings

- Inputs that different parsers might interpret differently

Conclusion

Formal language theory is not an academic curiosity, it is the mathematical foundation explaining why entire classes of vulnerabilities exist and why certain defenses work while others fail.

Key takeaways:

Regular expressions are regular. They recognize Type 3 languages and nothing more. Using regex to filter HTML, SQL, or JSON is mathematically impossible to do correctly.

Context-free languages require stacks. Parsers for JSON, HTML, and SQL must track nesting depth. This is why these formats can express structures that regular expressions cannot.

Turing machines are undecidable. No algorithm can perfectly determine whether arbitrary code is malicious. Sandboxing and behavior monitoring are necessary complements to static analysis.

Parameterized queries enforce grammar. They work because they separate the query structure from data values at the parsing layer, making injection impossible regardless of input content.

Parser differentials create vulnerabilities. When two systems interpret the same input differently, attackers can smuggle malicious content past security controls.

Parsers have broad security applications. From stealer log analysis to protocol dissection, grammar-based parsing provides robust, extensible solutions for structured data processing.

The goal of LangSec is precise: define the language your system should accept, implement a parser that recognizes exactly that language, and reject everything else. Within those boundaries, behavior is predictable. Security becomes engineering rather than guesswork.

References

- LangSec.org - Language-theoretic Security Project

- Chomsky, N. (1956). "Three models for the description of language." IRE Transactions on Information Theory.

- Hopcroft, J. E., Motwani, R., & Ullman, J. D. (2006). Introduction to Automata Theory, Languages, and Computation.

- Sipser, M. (2012). Introduction to the Theory of Computation. Cengage Learning.

- OWASP SQL Injection Prevention Cheat Sheet

- OWASP XSS Prevention Cheat Sheet

- Sassaman, L., Patterson, M. L., Bratus, S., & Shubina, A. (2011). "The Halting Problems of Network Stack Insecurity." LangSec Workshop. Available at langsec.org

- Rice, H. G. (1953). "Classes of Recursively Enumerable Sets and Their Decision Problems." Trans. Amer. Math. Soc.